- In a new book, policy analyst Nick Anthony unpacks the implications of digital fiat currency.

- Central bank research into CBDCs has quadrupled in the last four years.

- Anthony says technology is not the solution for a clunky cross-border payment system.

CBDCs will bring few if any of the benefits touted by the likes of the International Monetary Fund — and may pose significant risk to privacy and personal freedom.

That’s according to a new book, “Digital Currency or Digital Control? Decoding CBDC and the Future of Money,” by Nicholas Anthony, a policy analyst at the Cato Institute’s Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives.

“There should be no misunderstanding: Efforts in the United States and abroad are little more than a bid to solidify government control over money and payments,” he wrote.

Exploring CBDCs

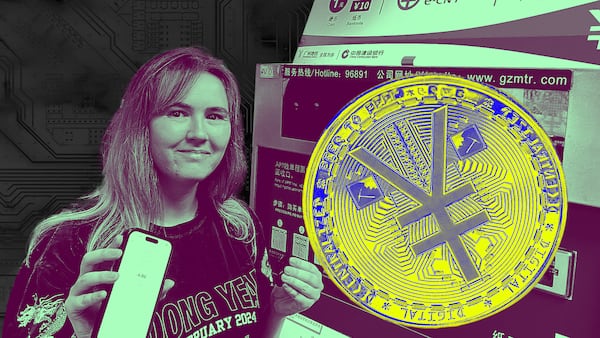

Interest in CBDCs, which stands for central bank digital currency, among monetary policymakers is increasing.

A total of 134 countries and currency unions are exploring CBDCs, almost four times the number in May 2020, according to the Atlantic Council.

That includes 19 of the G20 countries and the five founding members of BRICS, the club comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

China, which started evaluating CBDCs in 2013, has rolled out pilot programs in 25 cities.

Still, the projects have struggled to get off the ground. In China, merchants in pilot cities remain puzzled by what exactly the e-CNY — the digital yuan — is, and most people have only heard of it in passing.

The East Caribbean Central Bank’s prototype, DCash, suffered an outage from January to March.

And in the US, developing CBDCs has stalled amid growing concerns about how they might affect people’s rights.

Anthony says more needs to be done to ensure CBDCs don’t take hold in the financial system.

‘The problems that we have with the current cross-border system are based on policy choices.’

— Nicholas Anthony, author

“I am very worried and I think this is a real risk throughout the world,” Anthony told DL News.

He’s calling for people to start speaking up against CBDC projects.

“Because if that can happen now, we can very much change the outcome, both in terms of what final form that they take and whether people use them or not.”

What’s the point of a CBDC?

Anthony’s main argument is that there are few tangible benefits to countries implementing a CBDC.

“I’ve seen folks try to make the argument for financial and the like, but once you peel back to the next layer of that conversation and go into the details, it just doesn’t really hold up,” he said.

In the US, for example, 72% of the country’s 5.9 million unbanked households are simply uninterested in having a bank account, according to a Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation survey.

One reason is that they don’t meet the minimum balance requirements to open a bank account, while others are that they don’t trust banks or that they think they will enjoy more privacy without one.

There’s nothing, Anthony argues, inherent within a CBDC that would change this.

Indeed, the big problem in making cross-border payments more efficient doesn’t stem from technology, he said.

“A lot of the problems that we have with the current cross-border system are based on policy choices,” the author said. “The barriers that are currently up between borders are largely choices that federal governments have made.”

“There are other ways to solve this that don’t involve reinventing money, like reassessing the Bank Secrecy Act regime and relevant regimes abroad,” he added.

Programmable features

What really concerns Anthony is how CBDCs could control or restrict consumers’ financial decisions.

Last October, Lu Lei, deputy administrator of the State Administration of Foreign Exchange in China, advocated the use of “programmable features” in its CBDC.

And Thailand mulled a CBDC pilot that would have given citizens several thousand baht to spend, but restrict spending to within a certain radius of their homes.

Anthony offers the scenario of governments being able to cut down on excess drinking by limiting how many drinks a person can buy.

‘If they get rid of all those features for governments, and there’s no features for citizens, then what are we doing?’

— Nicholas Anthony, author

“These types of paternalistic policies may sound appealing for some at first glance, but can quickly fall apart or lead to unintended consequences. For example, how would it account for someone buying a round of drinks for a group of friends?”

More seriously, he added, it could also prevent people from shopping at legal but politically controversial businesses. Or even introduce negative interest rates to push people towards spending instead of saving.

“It opens up this new suite of tools that they didn’t otherwise have. However, those tools come at our expense,” he said.

Out of fashion

He said that discussing programmable features has fallen out of fashion with Western governments over the last few years.

“What we’ve seen is from 2016 to around 2021, those ideas were floated around quite openly. Now that we’ve had this slow rise of concerns, they’ve backtracked a little bit,” he said.

This has brought the argument for CBDCs into another “awkward space.”

“If they get rid of all those features that were going to benefit governments, and there’s no features that are going to benefit citizens, then what are we doing?” he said.

“It quite literally makes you scratch your head.”

Callan Quinn is DL News’ Hong Kong correspondent. Contact her at callan@dlnews.com.