- China's CBDC is in 260 million wallets and 25 cities.

- I tried it in hotels, restaurants, and the metro.

- How does it compare to AliPay and WeChat Pay?

The concierge at the Westin Hotel squinted at the app on my phone and nodded in recognition.

“Yes, you can use it here,” he assured me. “Everywhere will accept it.”

Then he backtracked. “Well, not everywhere, but most places.”

It was my first time back in mainland China in almost five years. Guangzhou, one of China’s largest cities, is only two hours by train from Hong Kong but it couldn’t be more different.

The architecture borders on dystopian. There are far more police, soldiers and other uniformed security on the streets. You need to put your bag through a scanner before you get on the metro. The pollution makes the city so foggy that you couldn’t see the tops of buildings. The food is much, much better.

I wasn’t returning just to see old friends. I also wanted to try out the digital yuan that I’d read (and written) so much about.

China has been testing its central bank digital currency, or CBDC, in select cities and provinces for the last few years, including Guangzhou and its capital, Guangdong.

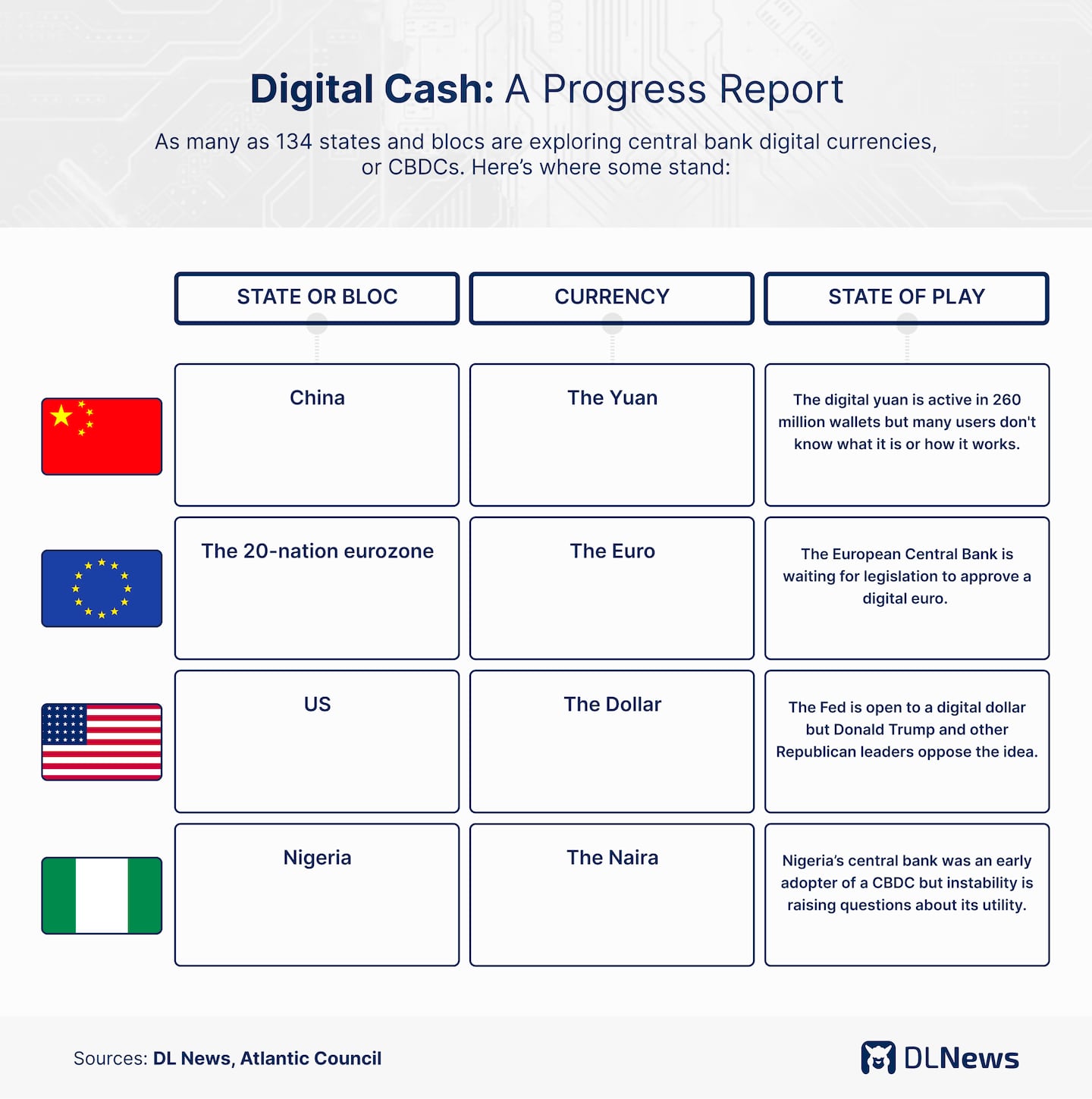

A CBDC is essentially a digital currency issued and backed by a central bank. Globally, 134 countries are currently exploring CBDCs, according to the Atlantic Council.

Largest pilot

China’s project is the largest CBDC pilot in the world, with 260 million wallets across 25 cities, (though it’s not public how many of those wallets have ever been used).

But CBDCs are also controversial.

Last year, a Chinese official floated the idea of adding programmable features into digital money. In an extreme case, a government could make money expire after a certain period of time, or control how money is spent.

A proposed CBDC pilot in Thailand plans to give citizens digital money to test but they can only buy things close to their residence.

Internationally, the use of CBDCs could allow nations to conduct international trade without using the US dollar, which is currently the global reserve currency.

“Dedollarization” or the end of the “dollar hegemony,” has long been a goal of China, Russia and other global players.

Even without the CBDC, China is probably the closest you can get to a cashless society. Few people use cash, and fewer businesses are willing to accept it without a substantial amount of grumbling.

Visa and Mastercard aren’t particularly popular (attempts to use a foreign bank card in the few places that take them generally results in the bank freezing the card).

Instead, it’s all about WeChat Pay and Alipay, both QR code-based payment systems.

I had heard the CBDC was off to a rocky start in China. Beijing started paying civil servants in pilot areas like the city of Changsha with digital yuan. But it doesn’t seem optional.

A few thousand people using a CBDC to buy metro tickets in Ningbo sounds interesting until you remember the city has almost 10 million residents. Uptake is a rounding error.

Creating an account

The CBDC app works the same as WeChat Pay and Alipay, but the features are more limited (you can’t transfer money to friends, and you need to top up instead of taking money straight from your bank).

I was unable to create an account pre-trip because you have to be in a pilot area first. Arriving in Guangzhou, I opened an account after several tries.

It required only a phone number, no ID (unlike other payment apps in China). When I tried to link my foreign bank card, I kept getting an error message that told me it was “out of service hours”.

Game over.

I finally managed to get it working via FPS, a payment method in Hong Kong that links to online banking apps. But if you didn’t have a Hong Kong bank account, that would be the end of your digital money adventure.

I chose a cute yuan-themed avatar for my account and set out to test it. The concierge at the Westin seemed somewhat confident that using the digital yuan would be just fine. But I set up Alipay as a backup just in case.

My first stop was a local family-run Lanzhou noodle restaurant. They only took WeChat and Alipay.

On the metro, I had my first success. The machines where you buy tickets had big e-CNY logos. So I bought a two yuan ticket to the Canton Tower, one of the city’s top tourist spots.

I tried to buy some milk tea at Family Mart, a convenience store chain. They didn’t take it.

At Canton Tower, the guy behind the counter had no idea what it was but tried to scan the QR code anyway. No joy.

At another restaurant, the manager told me that someone had once also tried to use it.

“Can try but it’s never worked yet,” he said as he tapped the QR code. It didn’t work.

Not very popular

In the CBDC’s defence, it is in the pilot stage and the places you can use it are limited. The government has never claimed it was available for use everywhere.

But what I found odd was just how few people knew what it was. I had to keep explaining.

The response was almost always a shrug and a “do you have WeChat or Alipay?”

At a tourist office, a staff member — he’d been dozing at his desk and I felt bad for waking him — said it “wasn’t very popular” and there weren’t many places you could use it.

An old acquaintance I ran into at a bar said he heard the café chain Luckin Coffee accepted it. It didn’t.

It was becoming clear that the concierge was wrong.

My friends seemed a bit bemused that I kept persevering with trying to use it.

“I just don’t really get it,” one said over drinks. “Why would I use it over Alipay? I don’t get what the difference is. Why is it different?”

For the user? Not a whole lot.

The White Swan Hotel

On the final evening, four of us headed to the White Swan Hotel for some tea. The hotel is where foreign dignitaries visiting Guangzhou stay, from Queen Elizabeth II and George W Bush to former North Korean dictator Kim Jong Il.

I tried to pay with the digital yuan one last time and practically started cheering when it worked. I was surprised — until I discovered the hotel is owned by the government.

Waiting for the train back to Hong Kong, I bought some tofu and tried to work out how to transfer my unused digital yuan back to my bank.

It’s a feature that doesn’t appear to exist yet. My bags now include 400 RMB ($56) of virtually unusable digital yuan.

Got a crypto story in Asia? Get in touch at callan@dlnews.com.