- More central banks are considering a digital currency for faster payments.

- But anti-CBDC protesters say digital currencies pose a threat to privacy.

- Privacy-focused design could allay fears of government control, CBDC supporters say.

- Here’s why CBDCs are coming worldwide despite the controversy.

“A CCP-style surveillance tool.”

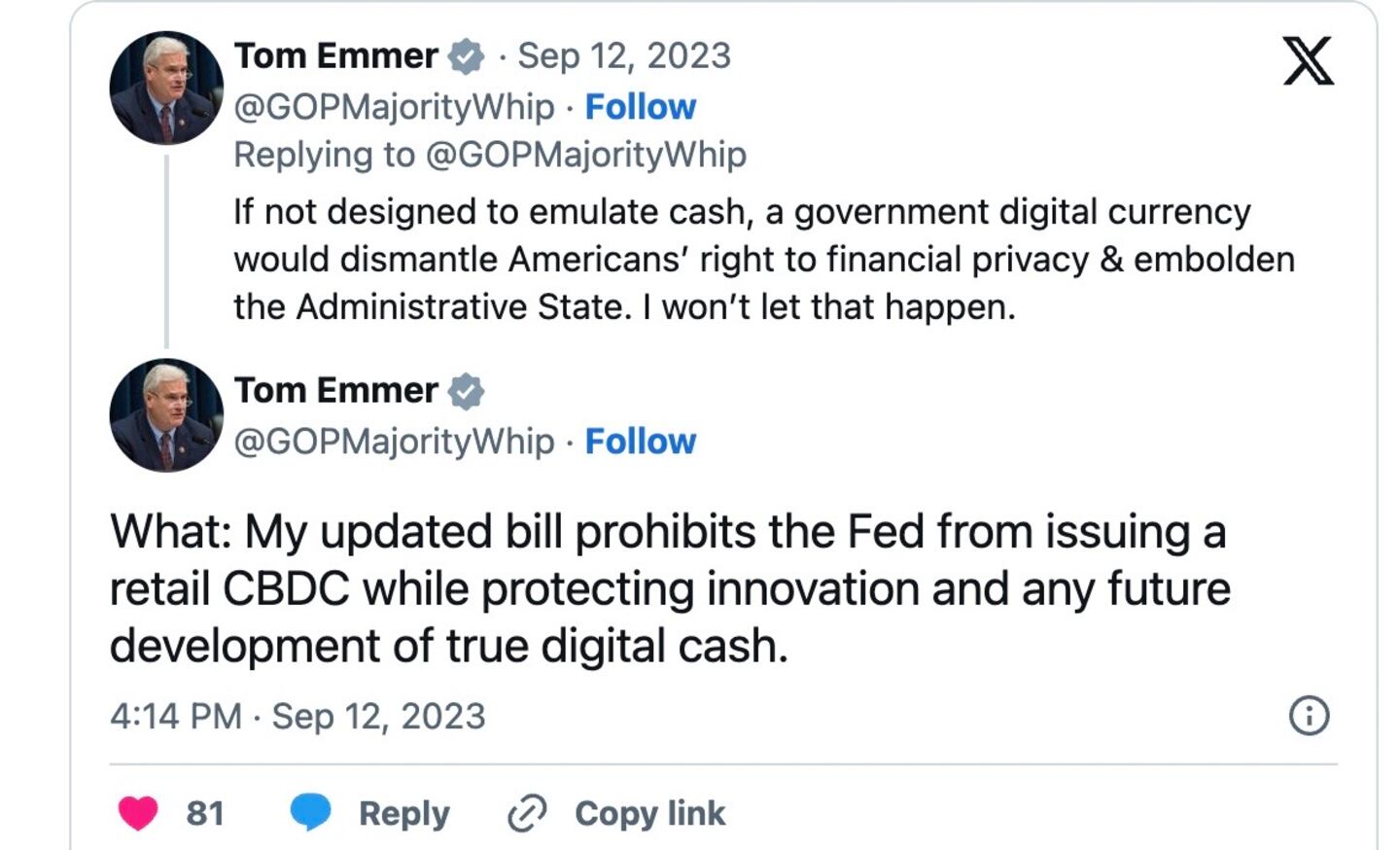

That’s how US Republican lawmaker Tom Emmer described central bank digital currencies — digital money issued by central banks — in a hearing earlier this month, referring to the Chinese Communist Party.

The comment from the majority chief whip in the House of Representatives — who is pushing a bill to limit the Federal Reserve’s power to issue a digital dollar — highlights the latest battleground in the culture wars.

On Wednesday, the House Financial Services Committee voted on Emmer’s bill and passed it for consideration to the full House floor. That’s a big step toward the draft becoming law.

Both Republicans and left-wing privacy advocates fear that CBDCs represent the threat of unprecedented citizen control.

But amid cries of protest from politicians and privacy advocates, the momentum behind CBDCs as payments and transactions move ever more online make them inevitable, say some experts.

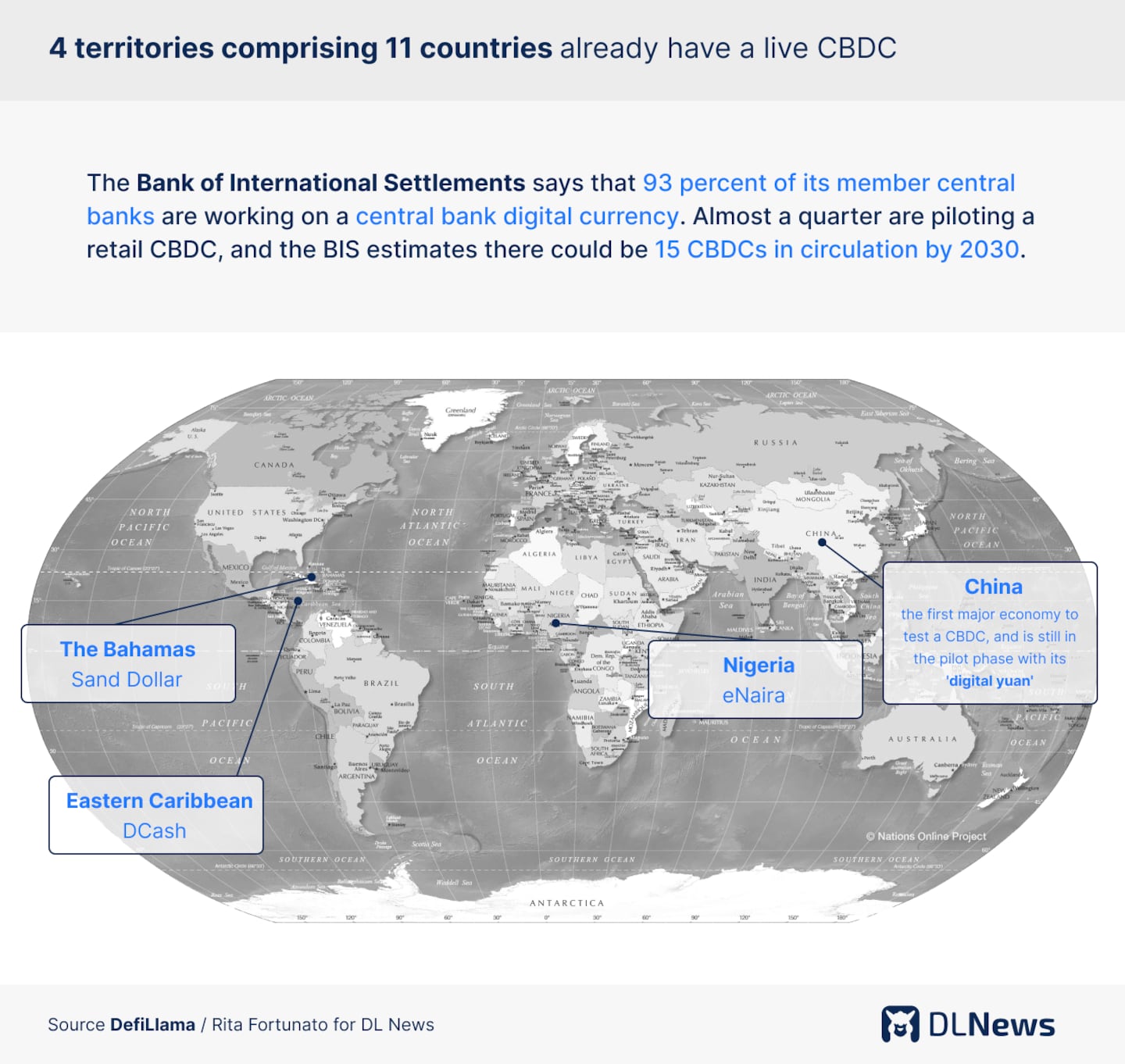

While only a handful of countries have launched digital versions of their currencies, some 130 countries are working on their own CBDCs [see graph below]. That adds urgency.

“The arrival of a CBDC is a matter of when, not if, and it is inextricably linked to the increasingly digital nature of our lives that necessarily implies a large and growing portion of transactions and payments are done electronically,” said Ryan Shea, a crypto economist at trading platform Trakx.

China, conspiracy theories and CBDCs

Some CBDC projects date back almost a decade, but many went into hyperdrive when Facebook announced plans to launch the Libra cryptocurrency in 2019.

“Libra worked as an eye-opener for many people,” Mithra Sundberg, the former head of Sweden’s e-krona project, told DL News in February.

The prospect of private mammoths launching their own digital money rattled central banks and governments, who feared it would jeopardise their ability to steer fiscal policy. European Central Bank executive Fabio Panetta raised a similar argument this summer when PayPal announced its new stablecoin.

Covid-19 served as a second accelerator. The pandemic pushed more payments online, intricately linking the idea of CBDCs to lockdowns and vaccines.

This also tied CBDCs to “plandemic” conspiracy theories, forming the flashpoint for protests, which have slithered into the rhetoric of Republican presidential hopefuls like Ron DeSantis, who has likened a digital dollar to “government sanctioned surveillance.”

Those statements are “just fear-mongering,” David E. Rutter, the CEO of R3, a blockchain technology business that has partnered with a dozen CBDC projects, told DL News, suggesting DeSantis was just vying for more votes.

But it’s not just tinfoil hats who fear CBDCs — there are legitimate reasons to worry, crypto experts say.

Legitimate concerns

Not only would CBDCs give governments visibility into citizens’ financial lives, but also allow them to control their access to their own money and what they do with it.

It doesn’t help that China, whose social credit system is a byword for dystopian government surveillance in the west, is piloting a digital yuan.

Shea is firmly in that camp. While banknotes are anonymous, digital currencies will necessarily come with identification and verification layers, he told DL News.

That’s for good reason — banks want to prevent financial crime — but it’s inferior to the privacy afforded by cold, hard cash.

Secondly, governments can easily apply smart contracts to CBDCs, giving them the ability to program money and give policymakers absolute control over the money supply, Shea said.

A government might choose to wield that power and overstep the bounds of what citizens in democratic countries consider acceptable.

It may, for instance, want to implement a health drive and bar some people from spending more than a certain amount per month on tobacco, booze or junk food, and set those limits in the smart contracts.

“Such policies may be well-intentioned, and may even result in better health outcomes, but it has a strong Orwellian whiff about it,” Shea said.

Central banks have rejected those concerns. Earlier this year, William Lovell, head of future technology at the Bank of England, said a proposed digital pound would not be a tool for spying.

“We don’t tell you how to spend your £10 notes,” he said. “We don’t want to tell you how to spend a digital £10 either.”

But CBDCs could get even more sinister: governments could cut off access of “undesirable” individuals to their own money, Shea said.

Governments and private commercial banks do this already, privacy advocates say, often citing how the Canadian government blocked the bank accounts of the so-called “Freedom Convoy” of truckers protesting a coronavirus vaccine mandate, and Coutt’s closure of accounts in the name of British far-right politician Nigel Farage.

However, the banking regulator said this week it found no evidence of systemic unbanking in the UK in an investigation launched in the wake of the Farage claims.

The devil is in the design

For many, CBDCs simply represent the natural evolution of payments as countries become increasingly cashless, that they may bring the unbanked into financial systems — a big draw for developing nations — and streamline services like welfare payments.

Jannah Patchay, the policy lead at the Digital Pound Foundation, which is pushing for a so-called Britcoin, told DL News that much of the CBDC panic is based on misinformation.

Her foundation advocates for “a CBDC design that respects and preserves privacy to at least the same extent that it is preserved in the existing accounts and payment systems,” Patchay said.

Privacy can be baked into the design of a CBDC through policy and the technology that underpins it, she said.

“Having a multi-pronged approach like this reinforces trust in the CBDC and helps to ensure that it cannot be misused — by any parties — in the future,” Patchay said.

The Bank of England’s mooted CBDC design, for instance, has third parties providing the wallet or accounts to consumers, and not allowing the government to access the transaction data.

While the BoE would provide the currency and central infrastructure, consumers wouldn’t interface with the central bank, but with wallets provided by private companies.

CBDC adoption slow

This may be a lot of noise considering that CBDCs haven’t gained much traction yet. While the Bank of International Settlements reckons that about 93% of its member central banks work on these projects, adoption of live CBDCs has been sluggish.

The UK and EU’s CBDC projects are both still in the consultation phase.

In the US, the Fed has said it won’t move ahead without clear direction from Congress and supportive legislation. But Republicans are not in favour — 60 of Emmer’s colleagues have signed on to his bill.